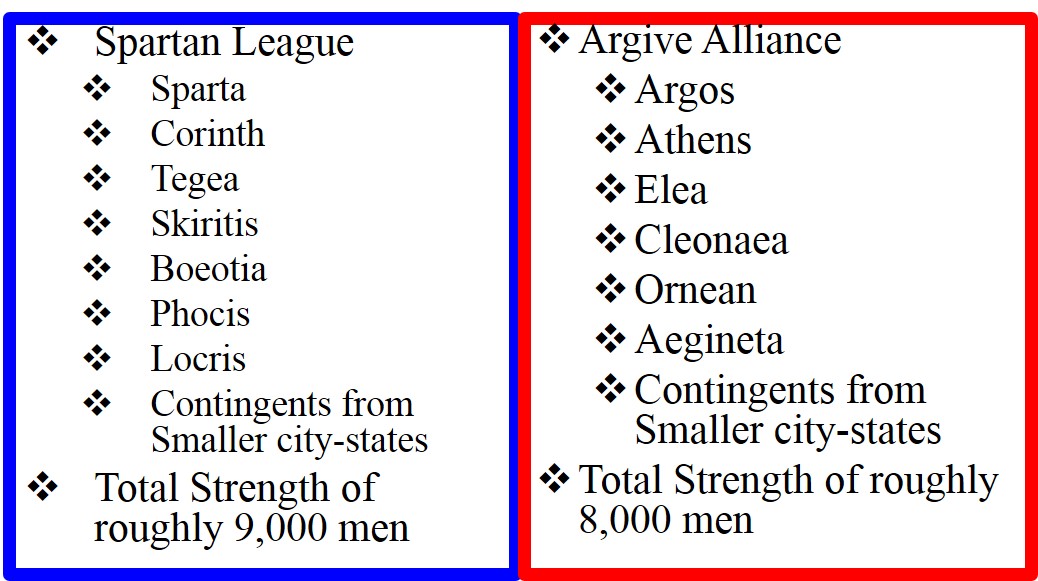

The Battle of Mantinea was part of the Great Peloponnesian War (430-404 B.C.). The war was fought in an effort to defeat and contain the growing power of Sparta in Greek Affairs. The war was ultimately a failure as Sparta won in the end and dictated terms to Athens and her allies in the process guaranteeing that Athens would not dominate the Greek world.

The prelude to the battle itself was a gathering of Argive Alliance troops who attacked Tegea, about 5 miles south of Mantinea. The Spartans rallied to Tegea’s defense and began to divert a stream to flood Mantinean territory.

The main source for the course of the battle is The Peloponnesian War by Thucydides. He covers the battle in Book V: 55-82 of his history. The actual account of the fighting is 65-74.

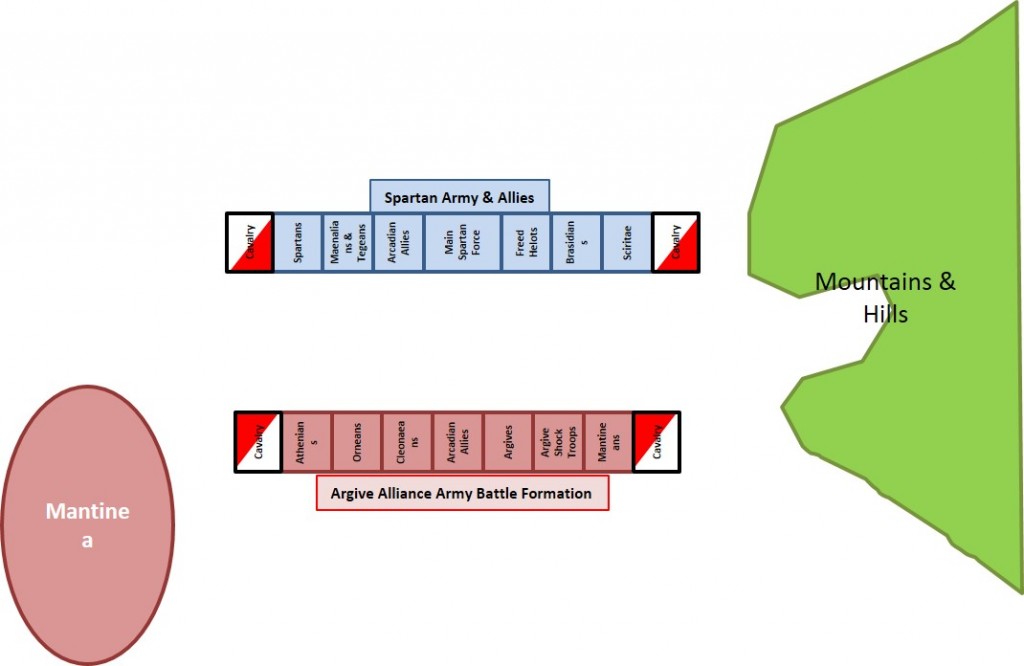

The battlefield itself cannot be pinpointed with any great accuracy today. However, based on the description of the location of various forces during the battle given by Thucydides it must have taken place to the eastern side of the Ancient Acropolis of Mantinea and the hills around ¾ of a mile away.

The preliminary to the battle was the Spartan army appearing near Mantinea arrayed in battle order. This startled the Athenian commanders who rushed to get their army formed and for defense. Once the armies were arrayed for battle the usual ancient pre-battle speeches were given and then both sides advanced towards each other.

The Athenians and Allies advanced recklessly screaming and shouting at the run while the Spartans displayed their usual discipline in battle by advancing at a measured pace to the music of flutes.

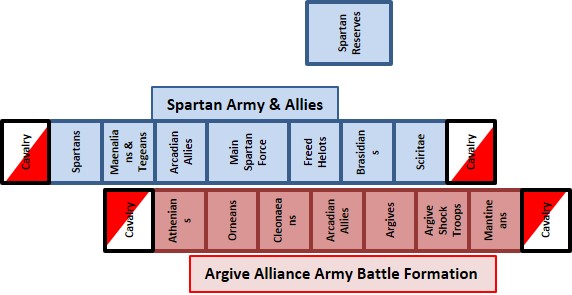

The evidence for tactical maneuver is in section 71 of Thucydides. He first explains the tendency of Phalanxes to move to the right as they advance; he then explains how the Spartan commander ordered the Sciritaeans and Brasidians to extend the line on the march while some of the reserve moved up to fill in the gap created by their movement.

This allowed the Spartan army to present a united front to the Athenians while the Spartan Right flanked the Athenian Left.

This allowed the Spartan army to present a united front to the Athenians while the Spartan Right flanked the Athenian Left.

That was the theory however it did not work out in practice as envisaged. Instead the Sciritae and Brasidians milled around without moving and thus created a gap that the Spartans were able to hastily fill.

As the two armies met the Spartans were initially driven back and a part of the Athenian line went on to ravage the baggage train of the Spartan army.

However, the Spartans led by King Agis soon rallied, attacking and driving in the Athenian line starting an instant rout where many Athenian troops fled without even striking a blow.

The Athenian cavalry stopped a slaughter by fighting a rear-guard action allowing the majority of the foot-soldiers to flee the battlefield. Casualties were also lessened because the Spartans declined to press their pursuit being content with possession of the battlefield itself.

Casualties

The casualty numbers come from Thucydides Book V: 74. The lopsided nature of the numbers is typical of Greek battles. Most of the Athenian dead were probably not killed in the initial clash but were wounded and then and later killed during the pursuit and mopping up by the Spartans and their allies. The Greeks did not generally practice ransom of prisoners in wartime.

Spartans – 300

Argive Alliance – 1,100

It should be noted that the vast majority of the casualties were probably dead (90%-95%) according to the analysis first proposed by Hanson in The Western Way of War: Infantry Battle in Classical Greece in 1989. Greek Hoplite warfare was extremely deadly because of the nature of the weapons used and the methods used to fight it.

References