The Allied invasion of Gallipoli and its subsequent failure represented perhaps the greatest lost opportunity of the First World War. There is every reason to expect that if the invasion of Turkey had been successful then much the same results would have accrued to the Allies then as were to accrue twenty-eight years later when the Allies successfully invaded Italy in the Second World War. The tangible results of the Allied invasion of Italy in 1943 was the capitulation of the government of Mussolini, and the diversion of up to sixteen German divisions in Italy that could have been more profitably used in France. Additionally, one of Germany’s most capable generals, Albert Kesselring was also tied down in Italy. If Kesselring had instead been in France it is conceivable that his operational creativity and flexibility could have made a crucial difference after Rommel was wounded in August 1944.

The Allies hoped that by successfully knocking Turkey out of the war they would open up a warm water route to Russia, divert German strength from the Western Front, and quickly conquer the Middle East thus freeing up western troops for service in France. The Germans had been supplying and advising the Turkish army and navy since before the war in hopes of completing the Berlin-Baghdad railway and thus simplifying their access to Middle East oil. The Allied invasion of Gallipoli in 1915 was a bold strategic move that if successfully executed could have changed the course of World War I. The assault only became a disaster through poor, unrealistic planning and operational mismanagement.

The Allied assault at Gallipoli could have been as successful an operation as the Allied invasion of Italy in 1943-1944 if only the Allied planners had appreciated the real possibilities of a realistically planned operation. The basic premise of both the Gallipoli and Italian campaigns was the same, namely to tie down enemy forces so that the war-winning blow could be landed elsewhere. The vastly different outcomes in similar wars almost demand a comparison of the factors that led one operation to success and the other to failure. There are many similarities between the concepts of the campaigns. Both Gallipoli and the Italian campaign were considered secondary, both were very much ad hoc, both were fit into the larger Allied war-plans as off the cuff operations, and lastly neither were seen as potentially war-winning from the outset.

The origins of the Gallipoli campaign lie in the combination of stalemate on the Western Front and the Russian reverses after their disastrous defeat at Tannenberg in the fall of 1914 and the entry of the Turks into the war in December 1914. The Western Front was seemingly locked in a stalemate without some innovation and it was felt that the Russians were on the verge of collapse after their massive losses at Tannenberg. The thought was that if the Dardanelles could be forced and a warm water route to Russia opened the Russians could be assisted and the danger of their collapse could be averted.

The idea of forcing the Dardanelles was initially put forth by Winston Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty in response to a request for a demonstration against the Turks to relieve pressure against the Russians. Thus the initial concept of the operation was as a simple demonstration by the Royal Navy to force the Dardanelles there was no thought of a troop landing in support of naval forces, it was only later that an assault by land forces was added to the plan. The Gallipoli campaign is one of the glaring examples in recent military history of what has become known as “mission creep” or the inevitable addition of tasks to what was originally a simple and straightforward assignment.

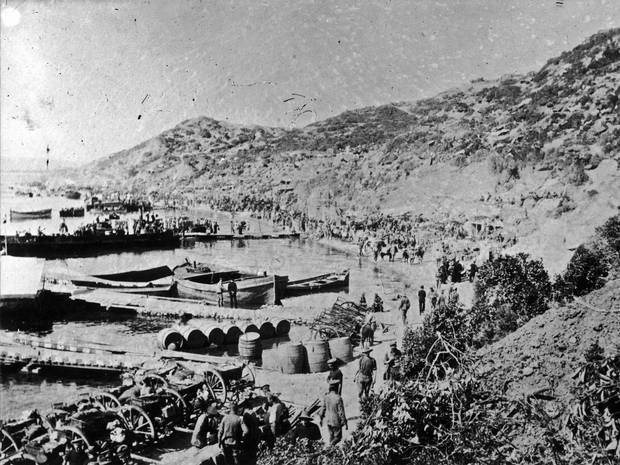

Planning initially began only for a naval attack to force the narrows at Gallipoli as Lord Kitchener, the British War Minister, said troops were not available for a land assault. The initial plan called for the Mediterranean fleet to force the narrows and break out into the Black Sea where they could harass and interdict Turkish coastal shipping in support of the Russian army. It was only after the Royal Navy’s failure in February 1915 with the loss of two capital ships that the idea of landing troops on the Gallipoli peninsula was batted around. After the idea’s approval, only two months of planning went into the operation and the assault occurred in April 1915, with troops hurriedly collected from the Middle East and the diversion of the ANZAC corps that was stopped en route to the Western Front and assigned to the operation.