The Battle of Antietam is interesting for several reasons the most important of which for me is that it is the single bloodiest day in American military history. There have been bloodier battles in American wars but no single day matches the blood spilled on those Maryland fields that early day in 1862. The Union victory at Antietam, if you can call it a victory, also provided Abe Lincoln with the opportunity to promulgate the Emancipation Proclamation. An executive act that was totally unconstitutional but that he did anyway for domestic and foreign political reasons.

Antietam was the final battle of Lee’s first invasion of the North and while it was not a decisive battle it changed things because of what came after. If anything, from a purely tactical and operational standpoint the battle was a draw. Both sides essentially beat themselves bloody over a few square miles of Maryland territory that neither considered vital. The battle is only considered a Union victory because Lee took his army and left instead of renewing the fighting for a second day leaving the Army of the Potomac in possession of the battlefield.

The commander of the 75,000 man, six Corps strong Union Army of the Potomac was General George B. McClellan. He was opposed the 39,000 man two Corps Confederate Army of Northern Virginia commanded by General Robert E. Lee.

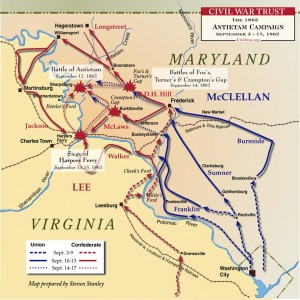

In the fall of 1862 following the Confederate victory at Second Manassas Lee decided to invade Maryland. There were several competing reasons for this decision. One was that it was thought that that best way to force the Union to a negotiated settlement was to inflict a defeat on Northern forces on northern soil. Another was the hope that by successfully taking the war to the North the Southern states could win foreign recognition and potentially aid. It was also believed that Maryland was the state still in the Union whose population was the most sympathetic to the southern cause. Lastly, Lee believed that by invading Maryland and threatening the capture of Washington D.C. he could force the Army of the Potomac under McClellan to accept battle on his terms.

The invasion began on 3 Sep. 1862 and almost immediately (McClellan was a notorious slowpoke) provoked a reaction from the Union forces garrisoned in and around Washington D.C.

Map Courtesy CivilWar.org

There were several skirmishes and minor battles prior to the culminating battle of the campaign at Antietam. The most significant of these was Stonewall Jackson’s capture of the federal garrison and Arsenal at Harper’s Ferry on Sep. 15th. This was the largest surrender of Federal troops during the war and the loss of weapons was considerable. The Confederates captured roughly 13,000 small arms, 200 wagons, and 73 artillery pieces when they took the Arsenal.

In the days leading up to the battle McClellan was slowly gathering all the disparate forces of the Army of the Potomac together and began to converge them west of Frederick in the vicinity of Sharpsburg. By contrast Lee’s army straggled in from their scattered positions in Maryland on 15 & 16 Sep. but McClellan’s habitual caution allowed Lee the time to consolidate his position prior to the Union assault on the morning of the 17th.

The first engagements between the two armies was on the night of 16 Sep when the Federal I Corps (Hooker) encountered rebel pickets.

During the night the Federal XII Corps (Mansfield) moved up in support of I Corps.

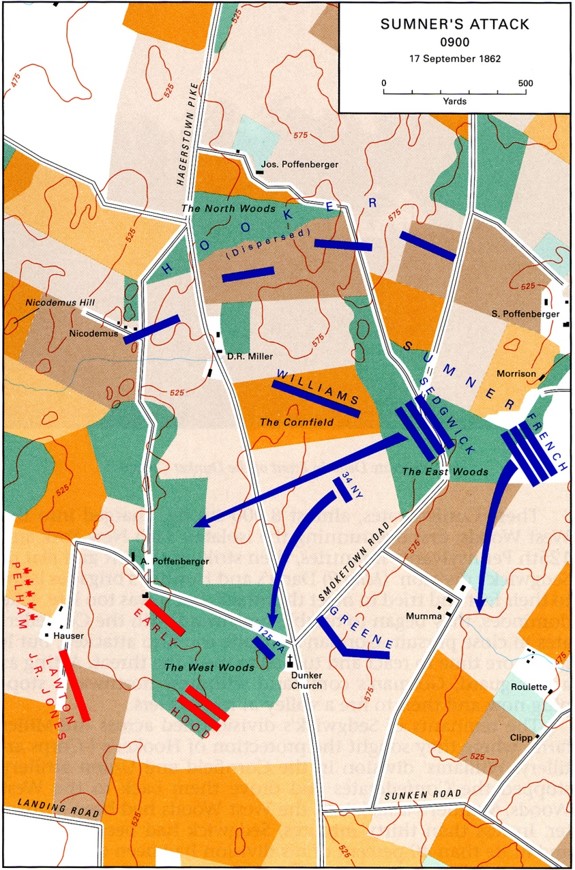

At around 0600 on 17 Sep Hooker’s Corps advanced and attacked the Confederate Left in the area of the North and East Woods and the Cornfield that was held by Stonewall Jackson’s Corps. The attack was almost successful until Hooker’s Corps was hit in the flank by Hood’s division who drove off the Union attack. As the I Corps retreated Mansfield was told that he was needed to cover the broken I Corps or the battle was lost before it really began.

As the XII Corps moved up to the attack Mansfield, it’s commander was mortally wounded and confusion briefly reigned as the 1st Division commander established his command of the Corps

At 0800 the XII Corps finally got into the fight and after heavy combat took and held the Dunker Church area unsupported by other Federal troops.

Map Courtesy USACMH

At about 0830 the II Corps (Sumner) entered the battle passing through the area where I and XII Corps had been so severely handled by Jackson’s Corps earlier. As the II Corps advanced into the battered formation of Jackson’s Corps they were hit in the flank by Fresh troops Lee had sent from his right and last Confederate reserves who managed to halt the attack in and around the Dunker Church and Cornfield. The failed attack by II Corps ended the first phase of the battle.

In the afternoon Sumner wanted to attack the Confederate left again because he believed the Rebels were more badly damaged than him and with the reinforcements from VI Corps he had the chance to

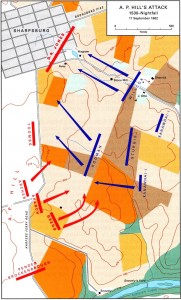

Map Courtesy USACMH

crush the Confederate left. The matter was referred to McClellan who denied permission for the attack and probably squandered the Union’s best chance to decisively defeat Lee’s Army, which was exhausted of reserves. The IX Corps (Burnside) begins to enter the battle around the Burnside Bridge at approximately 1300. At 1600 the IX Corps attacks towards Sharpsburg but the attack falters as the Corps is attacked in the flank by the Division of A.P. Hill and falls back to the bridge by 1700. This was the last major Federal assault of the day and ended the battle although skirmishing continued.

On 18 September both armies remained in position and Lee considered renewing the battle but taking his own casualties and federal strength into account he instead stars withdrawing his army south. McLellan chose not to pursue the retreating Confederates out of a belief that Lee was falling back on significant reinforcements.

Image: Library of Congress

With 3,782 dead and a total of 22,000 casualties out of 114,000 troops engaged the Battle of Antietam was the single bloodiest day in the history of American Arms. The next costliest battle I can think of that took place on one day and is continually mentioned is the D-Day invasion of Normandy. At D-Day the US had roughly 1,400 dead and a further 3,500 wounded out of approximately 80,000 invasion troops. Casualties at Antietam were roughly 19% while at D-Day they were 4.5 % of troops engaged.

An afterword is that an image was captured at Antietam that was a rarity prior to WWI. Namely, Alexander Gardener captured an image of the battle as it was happening. If you look at the below image on the left side you can see Union cavalry lined up awaiting orders and on the right side you can see the infantry of both armies fighting on the battle line wreathed in the smoke from artillery and their rifles. If you blow the image up you can even see a couple of places where men are dragging casualties away from the line. Why this has not become an iconic image of the Civil War I have no idea.

This article leaves out completely the fighting in and around the sunken road, which was the second phase of the battle some of the heaviest fighting of the day.